Our first night in the dessert is something of a wake up call, especially for MDS virgins like me with no experience of overnighting in a desert bivouac.

Having been in the hospitality industry for thirty years, I’ve grown to love luxury hotels. But I have also camped since I was a baby, including plenty of wild camping in some pretty rough places. Nothing like this though. It made me question the sanity of the four crazies in Tent 59 who had not only conquered this beast at least once before, but come back for another beating.

I’ve written previously about the inimitable Kevin Webber (AKA KEVLAA). Of all the humans I’ve ever met, Kevin ranks with the very best of them. Ask anyone who has met him and I guarantee they will tell you the same. This was Kev’s fifth MDS, on top of a daily running streak that had gone on for ever and other ultra endurance madness like pulling a sled through the arctic. Please, please, please buy his book, Dead Man Running – not because it will make him rich, but because it’s a bloody great book. If you want a signed copy, message me and I’ll arrange it. I promise you wont be disappointed. If you need a dose of positivity in your life, thirty seconds with Kevin will put you on the right track.

I hadn’t met Craig before, but we’d conversed in the preceding weeks and shared some good banter on our obligatory pre-race Tent 59 messenger group. Originally from Brummie-land, Craig now lives in Amsterdam and has also completed MDS twice. Like Kev, he was another invaluable source of advice, a voice of calm and encouragement. Craig also has the best toilet humour a tent mate could wish for and, as I was soon to find out, he become one of my two guardian camels. Only later did I learn about Craig’s back story. Long story short, he basically died while out running. Was dead for a while. Was resuscitated. And then became the first dead person to complete MDS. Twice. That’s quite a cool LinkedIn headline! Craig also has a book which I have yet to buy. I want a signed copy so a good excuse for a trip to Amsterdam. It’s called Die Another Day.

Is there a theme here?

Phil was on the far side of our tent (that makes it sound huge – basically the width of three people away) and we had a couple of things in common. Firstly Phil lived in Singapore, thence became known as Singapore Phil, so we swapped a few stories about Singapore, my family out there, Asian food we liked etc. Like me, Phil was an MDS virgin – ‘one and done’ he told me in his Scottish Singaporean accent. He was also one of the quieter ones in the tent but came out with the funniest one liners. His farts became legendary. Actually come to think of it, everyone’s farts were legendary. Within a few days when half of us had D&V1 and a dry fart was something to be celebrated. I kid you not.

Aaron was wedged between Singapore Phil and Kev. An American cousin, but living in Prague, he has shoulders and a chest built like a tank. I was very glad about that because his pack seemed to contain enough stuff to service a small island of the west coast of Africa. Maybe a couple of islands. Aaron had quite a dry sense of humour and from what he shared it sounded like he’d completed a lot of ultras previously. His bucket list was also impressively long.

Next to me on the other side was my great friend Rob. We met several years back at a Cancer Research UK London Marathon training day and have run many races together since, including London, Paris and Kaunas marathons, Race to the Stones 100k and South Downs Way 100mile ultras. Rob has also successfully completed MDS and if anyone was responsible for my trip to the Sahara, it was him. If I died it would be Rob’s fault. If I finish Rob would be taking the credit. If I got lost it would be Rob’s fault. If I took the wrong pills, it would definitely be Rob’s fault – as Chief Pharmacist at the outstanding Royal Marsden and an honorary professor, he was the closest thing we had to a doctor. As it turned out, Rob did deserve some credit for me finishing and indeed not letting me die. That would have been plain rude but he might just have beaten me (well on that day anyway). As I would later find out, Rob would become my other guardian camel.

Next to Rob were our younger tent mates. That’s not to say Kev, Aaron, Craig, Phil, Rob and I are old. Sarcastic comments at your peril. We are all aged within six years of each other and quinquagenarians (look it up). Richard and Simon were in their early thirties, albeit age has little to no bearing on success in this event as time would soon tell. Turns out that as well as good ultra runners, Rich and Simon were also bloody good rowers by the sound of things. Interestingly, not the first time I’ve heard that rowers make bloody good ultra-runners: Beth Pascall and James Cracknell are perfect examples. I got the sense chatting to them about rowing that the training is pretty brutal. Note to self, perhaps add a rowing machine to the training mix? Rich and Simon knew each other and also knew Anna next door in Tent 60 – another rower and pretty handy ultra runner, who Rob also knew. Small world these ultra runners…..

Rich was another of the four in our tent who had completed MDS previously, yet another knowledge bank to dive into. I’m pretty sure Rich also had the heaviest pack in our tent. Admittedly he is built twice as big as me, but I doubt I could have dragged that weight round more than a couple of stages.

Every tent has to have a ‘fastest runner’ and in Tent 59 that was definitely Simon. When he proudly declared he’d been off the booze for six months, it was clear he was here to compete. I might run a lot but I also like a drink way too much to go six months dry. Kudos, Simon had an absolutely cracking race despite the challenges we all endured with the heat and D&V. Going into the race, I had also wanted more than just to finish and had high hopes of a top two hundred placing, perhaps even top one hundred. Fortunately, I’ve learned over years of running how to adapt and adjust both expectations and approach, sometimes mid way through a race. That adaptability would become paramount (gross understatement). In a matter of hours, we would all be tested to an extent none of us could have imagined. For differing reasons, survival would shortly become the primary (and in my case only) goal.

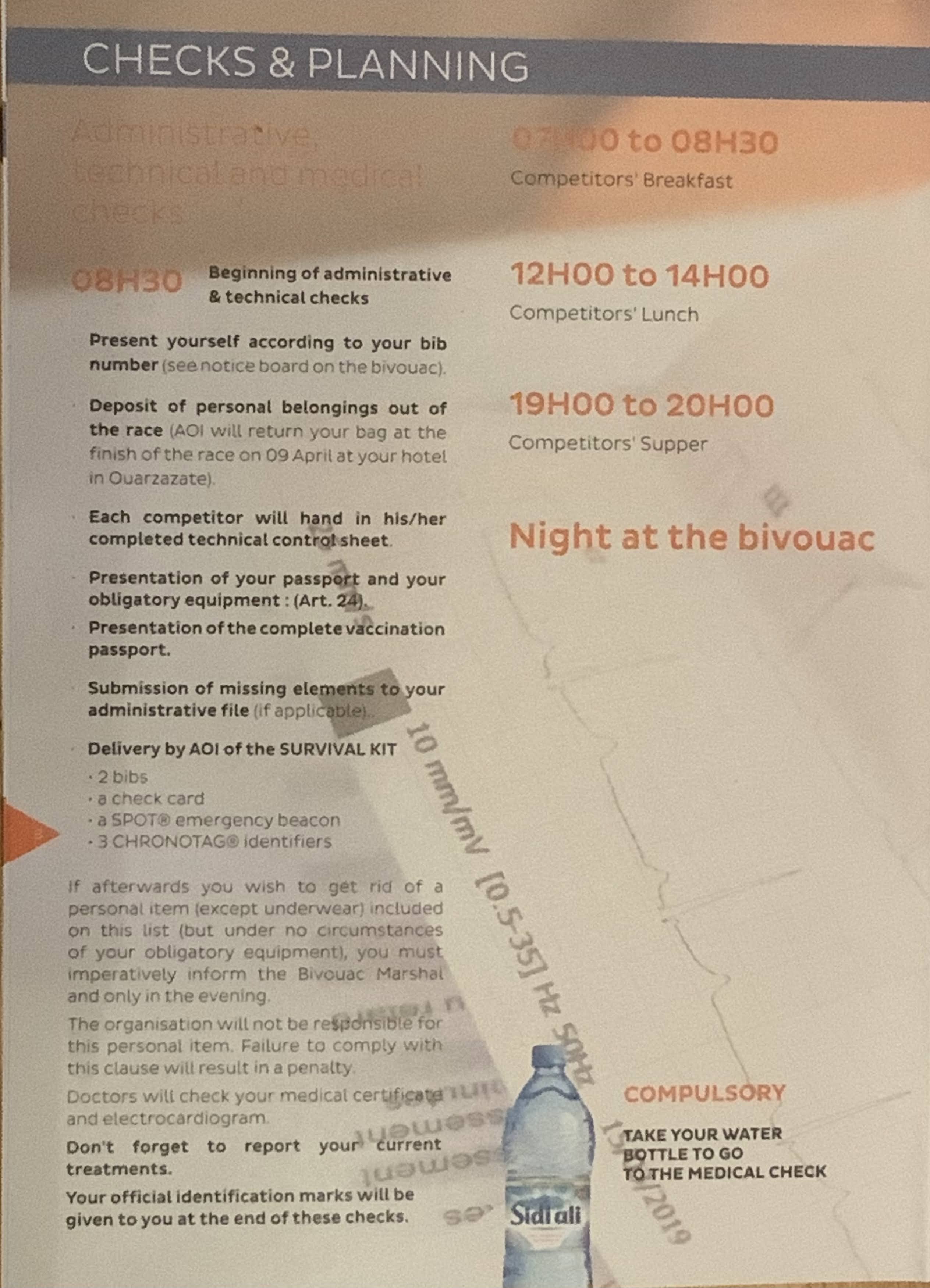

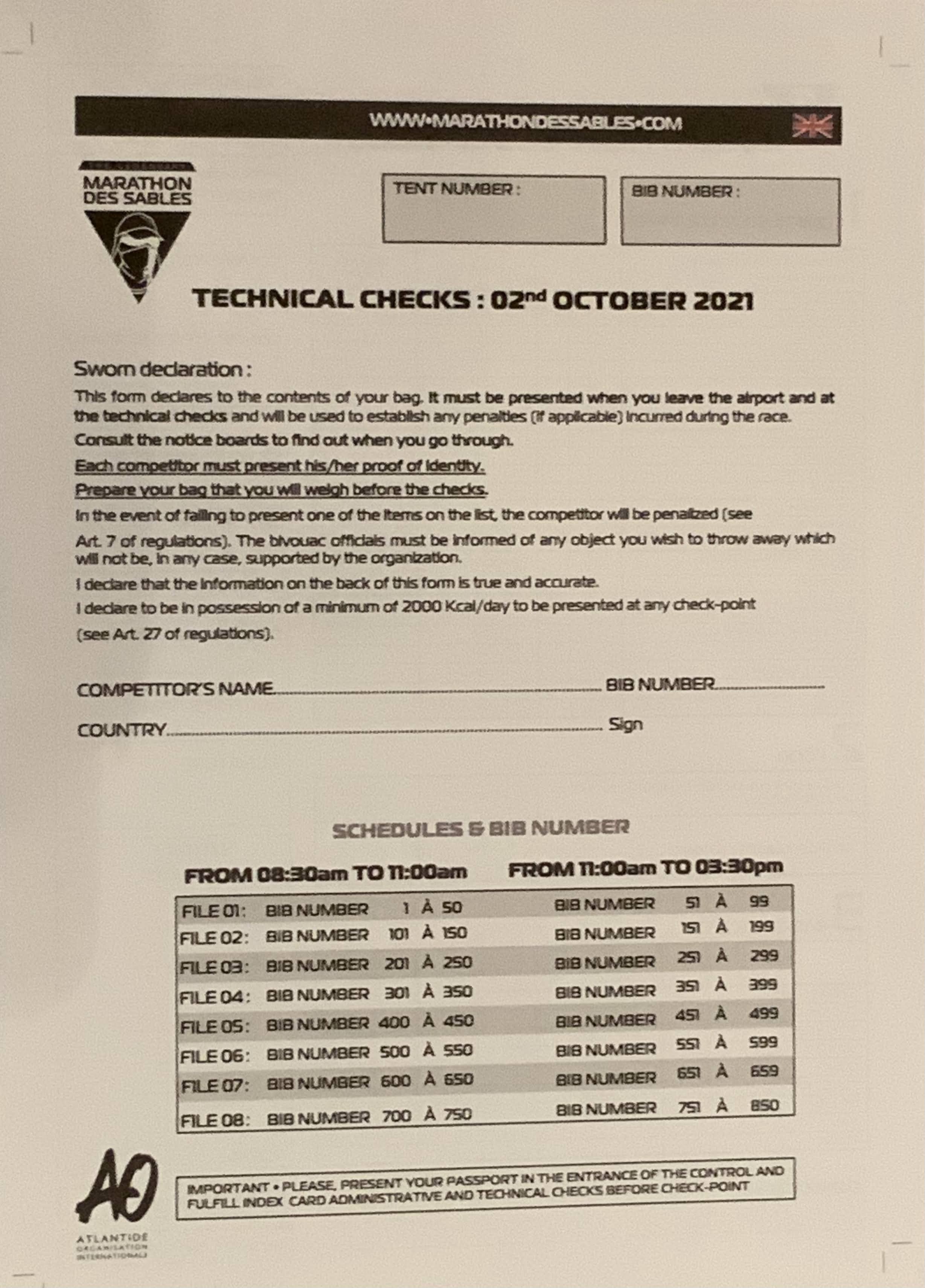

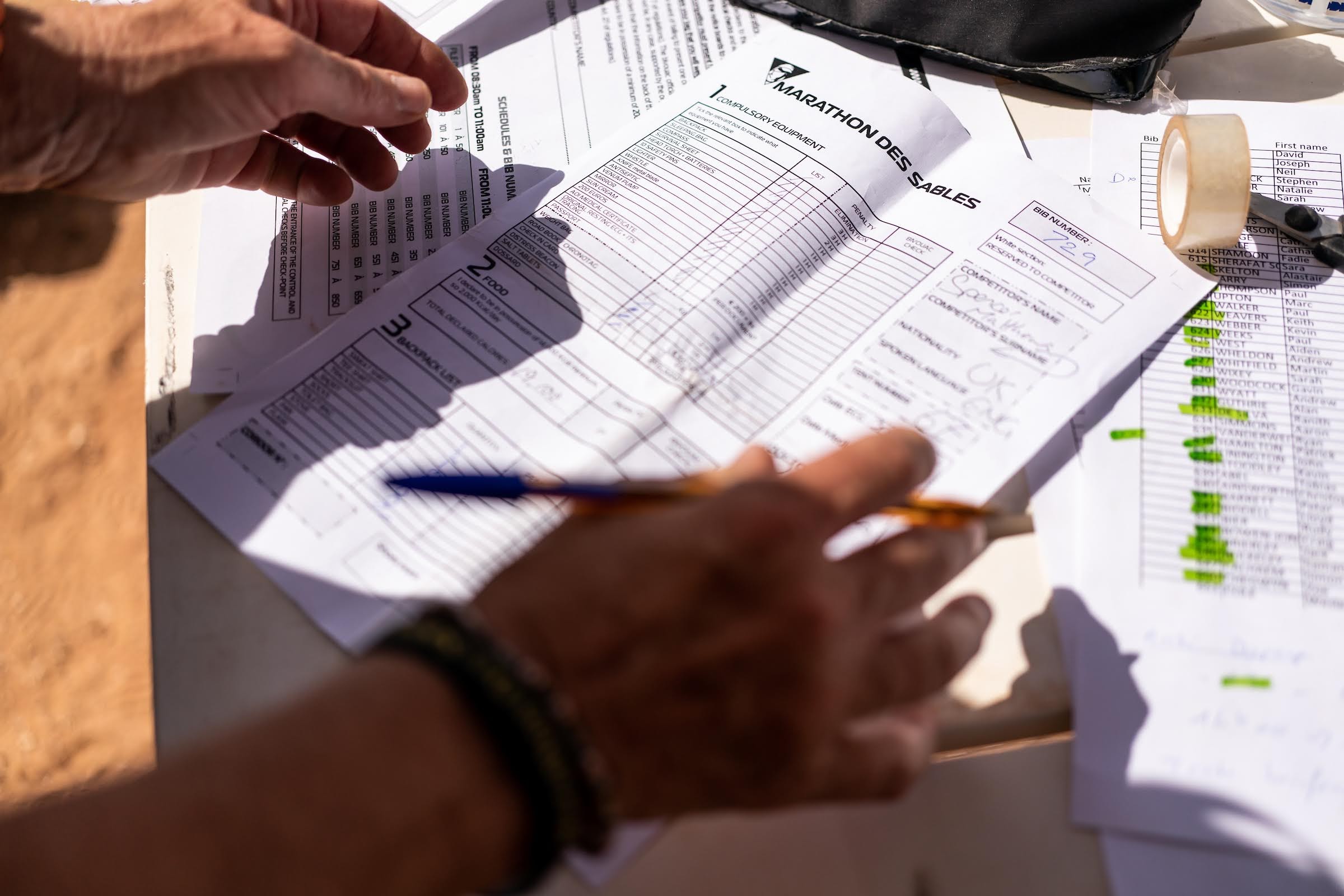

After breakfast, the last thing standing between us and the start line were the ‘administrative, technical and medical checks’. To be clear, some people have previously fallen at this final hurdle so most of us were a little on edge. Participants are required to present themselves according to bib numbers, hand over several things and are given several things back. Ahead of this, some final frantic packing and repacking of race packs was taking place. As the day heated up, so did the atmosphere……and the apprehension.

For me, several last minute changes ensued. At this time of year, the temperature at night is ordinarily very cold and necessitates both a decent sleeping bag (Yeti Passion One Ultralight Down, less than 300g) and a jacket (Salomon Outspeed Down 271g). After the first night, it was clear that temperatures both day and night would be significantly higher than anyone had anticipated or previously experienced. The sleeping bag was mandatory. The jacket was not. Out of my pack went the down jacket, a pair of Tyvek trousers (only 71g but no longer necessary), my third buff, a lightweight power pack, charging cables for iPhone, Garmin and MP3, a couple of emergency cable ties and some food.

The first thing you have to do is deposit your personal belongings out of the race i.e. everything that is not accompanying you on your 250km thrill ride. There is something just a little scary about giving your bag away. Once you let go, that’s it. It is taken and locked away at your hotel in Ouarzazate and whatever happens, the only way you get to see it again is by finishing or withdrawing. Sayonara!

I mentioned in my first blog that the MDS organisers are unapologetically, French! Well, it is after all a French event, founded by a Frenchman, supported by French medics, French logistics and…….that very special breed of French administration. The ‘je ne sais quoi’. We were about to experience je ne sais quoi as we queue for over an hour in the blazing sun. Was this a subtle means of acclimatisation?

Next you hand in your completed Technical Control Sheet. Not the easiest thing to decipher, so I ended up with lots of scribbles and crossing out all over mine. The scoop was as follows:

‘If afterwards (i.e. after handing in the sheet and having your bag weighed), you wish to get rid of any personal items (except underwear) [er, like I had any underwear 🙄] included on the list (but under no circumstances any of your obligatory equipment), you must imperatively inform the Bivouac Marshal and only in the evening. The organisation will not be responsible for this personal item. Failure to comply with this clause will result in a penalty’.

Translation: If you want to ditch non-mandatory crap you decide you don’t want to carry for 250km, don’t hide it in the bottom of a bin bag or leave it in the desert. Give it to one of the French ladies because the Berbers will be grateful for your old socks or a discarded power bank (but not your old pants). If you don’t and we check and we catch you, it will cost you a time penalty or maybe €100. We haven’t decided yet. Of course we won’t check, but you’re shitting yourself that they will check. So you duly comply.

Bon. C’est ça!

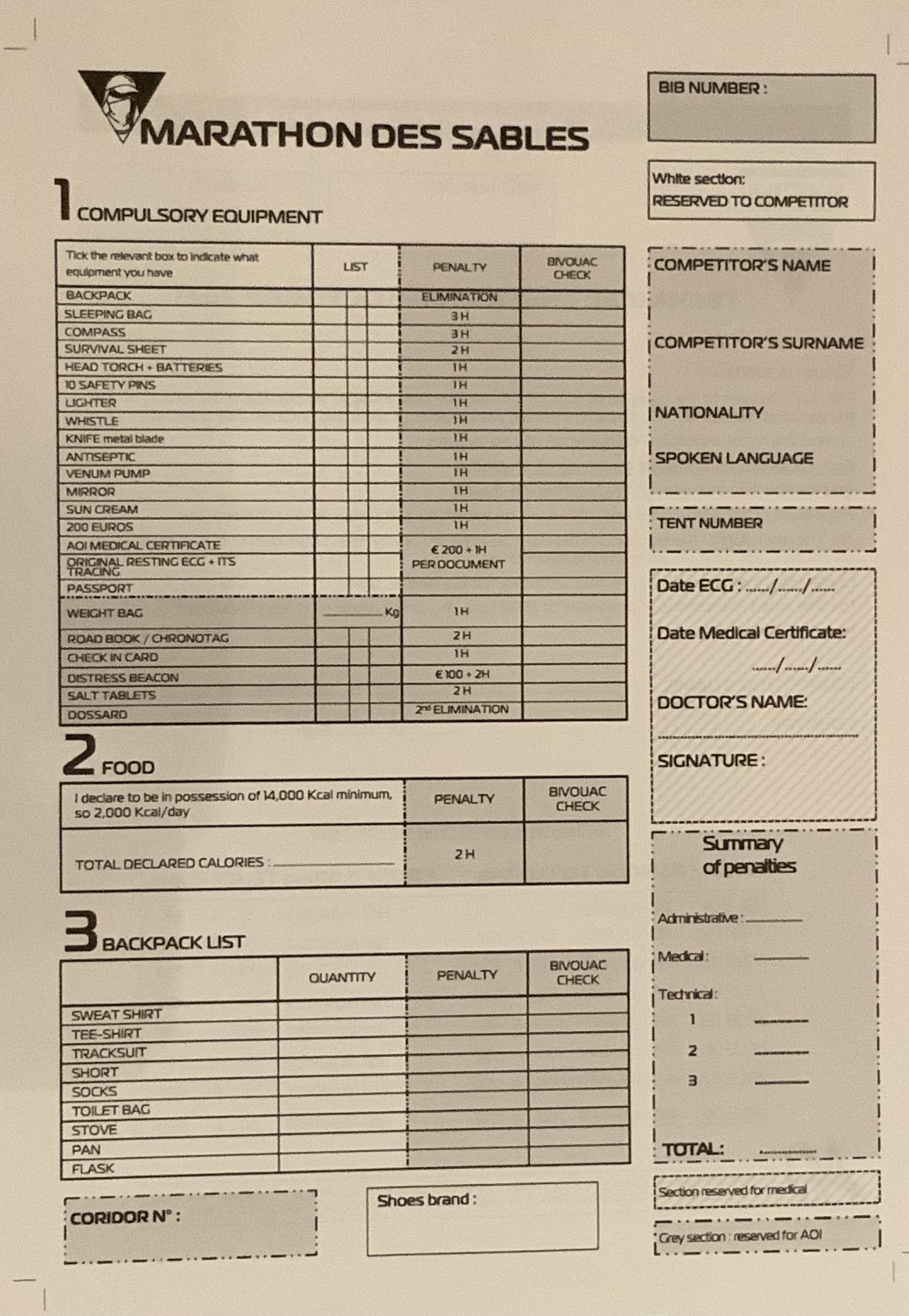

In addition to the standard mandatory items – most of which you’ll never use, but sound good (anti venom pump, signalling mirror, aluminium survival sheet…etc) some additional protocols were put in place because of COVID-19. These required us to have thirteen face masks and minimum 50ml of alcohol gel. As it transpired both became extremely important. More on that later.

After presenting passport and vaccination certificate, our packs with the obligatory equipment and food are then weighed. This was the point at which the administrators may have checked the mandatory kit and food with a fine tooth comb. For the majority of participants, this is a tick box exercise. Everyone had signed in blood that they had everything required, the threat of a time penalty or fine was deterrent enough. For the elite runners and those with a bag weighing spot on 6.5kg, it may have been a different matter.

For me, the weigh-in was my first big win. My pack was a measly 6.85kg, excluding water, salt tablets, the GPS SPOT tracker and check card. My target was sub-7 so with those extras I would meet my goal. Get in there 👊 I win the prize for the lightest pack in our tent. The absolute minimum allowed is 6.5kg but very few people get that low. I would have needed to cut off every strap from my race pack, ditch all luxury items (MP3 player, earbuds, CRUK flag, second running shirt and pair of socks), plus pretty much everything that was not mandatory or edible including my sleeping mat, Co-codamol and paracetamol….and my iPhone which remained switched off and served only as a camera. In the event, iPhone refused to turn on past noon when the heat was most fierce and eventually went on strike, demanding cooler working conditions.

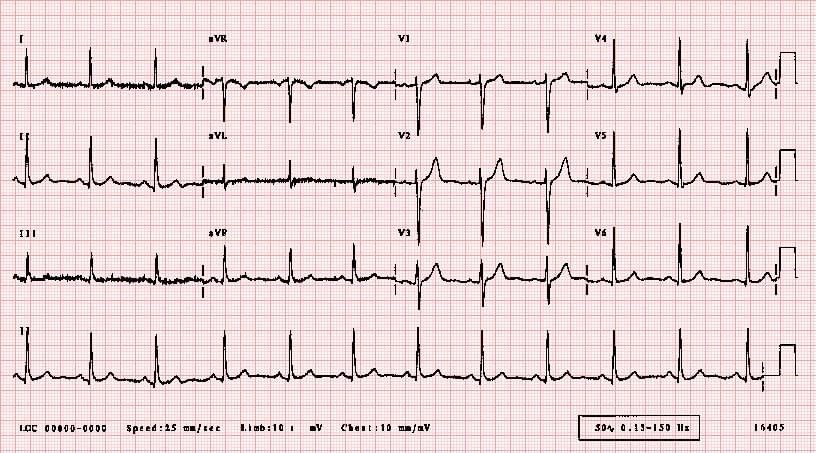

Next we are required to hand over our original, dated, signed ECG and medical form; this is where things can get dicey if anything is untoward. Rob had mentioned the previous time he did MDS, a guy next to him had a dodgy ECG and was withdrawn from the race on the spot. This year, one lad had an ECG which had been incorrectly dated. No amount of pleading worked. Though he was not excluded, he had to take another ECG – no doubt with a €100 administration fee.

In return you are given a little bag full of salt tablets, coated to make them easy to swallow. Not to stress the point, but these can be considered life-preserving pills. I’ve used all sorts of hydration stuff before, electrolytes and the like. In ‘normal’ conditions I drink very little when I run and can happily finish a marathon in cool climates with a couple of isotonic gels and no water. But this is anything but normal. In fact this is not even normal for the Marathon des Sables. This is hot. Hotter than hot. For context, one of the participants had a digital thermometer which he put out in the midday sun. When it reached 65˚C, it exploded. It is very, very hot.

The lovely French medic interrogating my ECG gave crystal clear instructions for the salt tablets:

‘Take one at the start of a bottle, another when you have drunk half of it; do not drop them in the bottle as they just fall to the bottom’.

Understood.

Our next gift was two bib plates with timing chips attached to the rear – not the paper ones you get at road or track races. These were super tough plastic, designed to withstand a week long beating in the Sahara. Our penultimate present was a water card on a retractable cord, or as Kev called it, a zup-zup. Somehow, having safely chaperoned my zup-zup round the Moroccan Sahara, to Ouarzazate and back to the UK, it disappeared before I got home ☹️ Whoever pinched it from my pack, may you be cursed by the Sands of the Sahara and wake up with a scorpion in your pants. [Edit: Sat 20th Nov: turns out Rob picked it up and has it 😂].

Our final gift was the super important GPS SPOT tracker. Not only was this critical for safety and to raise an SOS (as some participants would sadly need do) it was also key for friends and family dot watching and tracking us. As I later found out, this became a daily pastime for many of you – indeed I bumped into my amazing MP Helen Hayes shortly after I arrived home, who informed me she had been avidly tracking my progress. I was supper chuffed to hear that!

I knew it was important that the SPOT tracker was both well affixed AND comfortable. When your shoulders and collar are as bony as mine, this is important. As it turns out, neither would be the case. By the time I walked back to our tent, one of the two zip-ties the administrator had used to attach it had snapped (lovely French lady had tried to save a little too much of the zip-tie). A return visit and a several lengths of gaffer tape did a better job. However as my right shoulder can now attest, it was not particularly comfortable. Of all the pain I had during the entire event, my shoulders came off worst.

As the afternoon ticks on, the apprehension steadily grows. Rumours circulate that three people are already on IV drips. The race has not started yet. It is hot. Bloody hot.

We lie around all afternoon conserving energy, swapping lavatorial jokes and good banter. Our bivouac marshal passes by and we are given advance notice for the traditional pre-race photo gathering. Images of the bivouac taken from a helicopter or drone have become iconic, with participants gathered together to spell out the edition number and Patrick doing his stuff.

First visit to the toilet goes off without a hitch. Biodegradable shit bag does its job. Another win, even though I didn’t pay attention to the demonstration by Patrick’s sidekick on the roof of the Land Rover yesterday.

I only just resist the temptation to take a beer at our final ‘real’ dinner. Cold beer. So tempting.

Soon we are falling asleep (not) to the rhythmic beats from our Spanish friends opposite. I get that our Southern Mediterranean cousins like to party late into the night. But I am unsure if they realise we have a little bimble in the jaws of a raging furnace to deal with in a few hours. Remind me how you say ‘OK, enough already, can you pretty please shut the f**k up’ in Spanish?

Notes

1. Diarrhoea and vomiting.

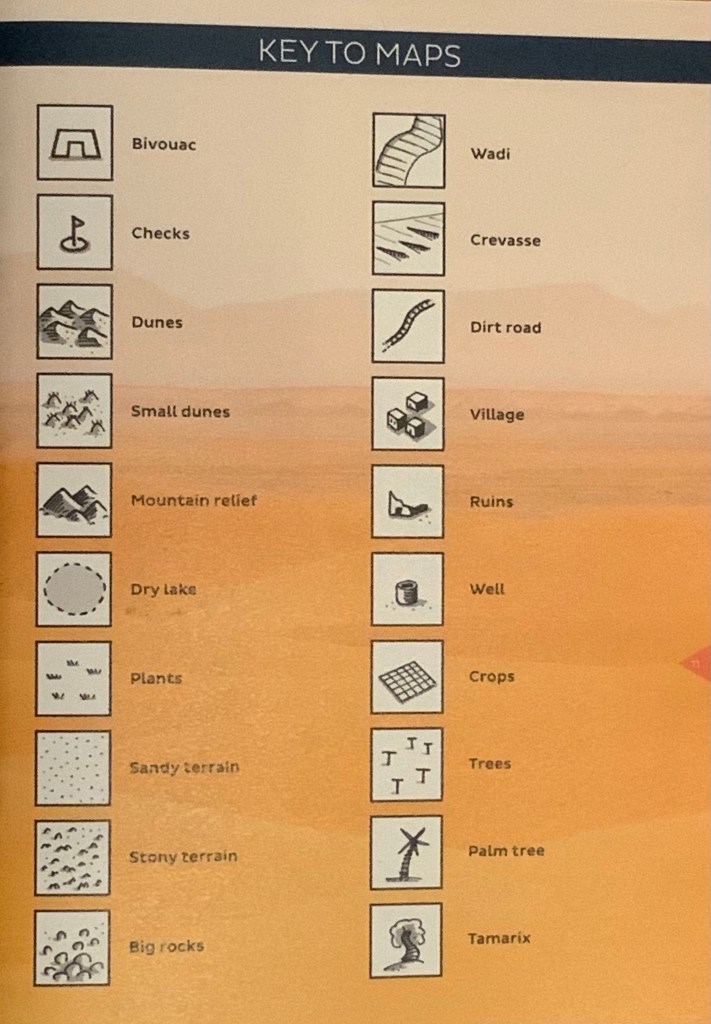

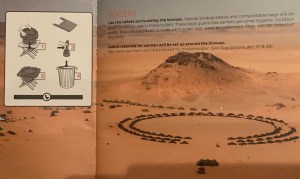

Before we get into the actual race in my next blog, a little more about the Sahara and couple of terms. See also the picture titled ‘Key to maps’ below.

Marathon des Sables: Literally translated means marathon of the sands.

Sahara: The word Sahara is derived from the Arabic noun ṣaḥrā meaning “desert”. Sahara is also related to the adjective ashar, meaning “desert like”, referring to a reddish colour. I am still washing reddish colour out of everything!

The Sahara (الصحراء الكبرى, aṣ-ṣaḥrāʼ al-kubrá, ‘the Greatest Desert’) is a desert on the African continent. With an area of 9,200,000 square kilometres (3,600,000 sq mi), it is the largest hot desert in the world and the third largest desert overall, smaller only than the frozen deserts of Antartica and the northern Arctic. For context, the 9.2million m2 is similar to the US or China and 8% of the earths land area.

It is one of the most inhospitable places on Earth, temperatures reach 50 degrees C / 120 degrees F by day (in the shade….. except there is no shade). Because of the lack of humidity it can plummet to freezing at night……except it was exceptionally hot so never got that cold. It receives less than 1 inch of rain a year.

The Sahara is much more than just sand – in fact, the majority of the Sahara is made up of barren, rocky plateaus, as well as salt flats, sand dunes, mountains and dry valleys.

Erg: An erg is a broad, flat area of desert covered with wind-swept sand with little or no vegetative cover. The word is derived from the Arabic word ʿarq, meaning “dune field”.

Jebel: (In the Middle East and North Africa) a mountain or hill, or a range of hills. It is a common misconception that the Sahara is just sand.

The largest dunes in Morocco are the Erg Chigaga – with some dunes reaching a massive 300m. The Chigaga dunes are hard to reach, with access only permitted by 4×4, camel or foot.

The Sahara used to be lush and green, home to a variety of plants and animals. Change came approximately 5000 years ago, due to a gradual change in the tilt of the earth. It is thought that the Sahara Desert will become green again at some point in the future.

People who live in the Sahara are predominantly nomads, who move from place to place depending on the seasons, whilst others live in permanent communities near water sources.

Wadi: (in certain Arabic-speaking countries) a valley, ravine, or channel that is dry except in the rainy season.

Oued: is the Arabic term traditionally referring to a valley. In some instances, it may refer to a dry (ephemeral) riverbed that contains water only when heavy rain occurs.